NB: Jit Singh Uberoi was beloved of many of us who were not students of sociology. My personal link with him was not slight: he was on the interview committee which appointed me to a teaching position in Ramjas College, in August 1974. Thereafter we met and interacted in academic seminars as well as on grievous political matters (the aftermath of the Delhi carnage of November 1984). He was a man always affectionate and friendly; and whose wisdom was gentle and profound. Many of us will miss him, and cherish his memory. Goodbye Professor Jit; thank you and rest in peace. Salaam.

My first encounter with professor J.P.S. Uberoi was after completing my B.A. in history at a lecture designed to entice potential students into the Department of Sociology at the University of Delhi. He was mesmerising in his elucidation of ‘sign, symbol, and symptom’ and was successful in converting several students, including me, to sociology. I went on to pursue my M.A. there and remained under his guidance as my research supervisor for 13 years, despite my inclination to work full-time in the theatre. This was due to his mesmerising personality, his overturning of my former worldview, and my desire to contribute to the advancements in the new fields of thought he had unveiled.

During most of his teaching years, he was clad in shorts – with the addition of a string tie on more formal occasions. If asked, he would retort that it was to denote that he was a professor and not a bureaucrat. He was certainly not a bureaucrat nor average in any respect, ever blending his puckish sense of humour with professorial gravity. Ready for any adventure, he once accompanied me on a bicycle trip in the environs of Poona where we ended up sleeping on a dining table under a narrow roof in a raging storm.

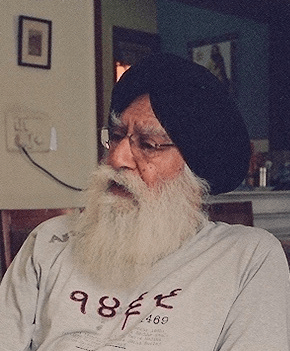

On another occasion, he came unannounced to Poland – then on the other side of the iron curtain – and managed to track me down in a remote mountain village where I was performing, intriguing everyone with his snug black turban. Those were the days without mobile phones or computers when landlines didn’t function, and trains were choc-a-bloc. Being vacation time, no seats were available on the trains, but I am told his compelling eyes worked their magic with the ticket lady.

He was the only academic I have ever known whose life and thought were wholly united. Occasionally, one would ask what one considered a private non-academic question and would be immediately jolted back into considering the matter at hand through the more rigorous prism of analytical thought. As Shiv Visvanathan once said, he could talk for an hour on the sociology of the tomato that he discovered on his plate. Even when in hospital during his last days, when his body was failing, his mind remained ever sharp, actively analysing the medical industrial complex he found himself a part of and trying to educate his nurses about what they were supposed to be doing.

The range of subjects that engaged him and that he wrote about were phenomenal. They ranged from the atom bomb to socio-linguistics, from Sikhism and Islam to the structure of the modern university, from swaraj to the life of things, from the nature of frontiers to the theory of colours, from martyrdom to the industrial worker, from civil society to the semiotics of modern science, from the theory of Trobriand potlatch to Andarabi social structure, from the rainbow to the Eucharist. I absolutely agree with a reviewer of one of his books who wrote that his work was of such originality that there was nothing with which it could be compared.

What turned my personal worldview was particularly his analysis of Western civilisation and the modern university which most took for granted at the time. It was eye-opening for me to be able to look at modern Western Europe, its systems of knowledge and educational institutions (to which we ourselves belonged) through an independent prism of sociological scrutiny. We learnt that the same binoculars through which European anthropologists had looked at non-Western cultures could be turned the other way.

He established, despite much opposition, a European Studies Programme at the Department of Sociology. This was not intended to be yet another variation of regional studies but a laboratory for new Indian perspectives on Western theories and practices with sociology and social anthropology viewed and understood as a single spectrum. Sadly, this project remained misunderstood and unappreciated and was abandoned by the next generation of departmental governance.

Uberoi held one of the longest professorships at the Delhi School of Economics and, as a result, nurtured several generations of students with equal doses of love and severity. Students loved and flocked around him even if they didn’t quite understand what he was all about. They were simply fascinated by the phenomenon of such a man. He was witty, charming, and uncompromising. His upstanding principles and aversion to compromise cost him many opportunities which others, less burdened by ethics, would have eagerly seized.

For instance, if he received an invitation to lecture on a subject that demonstrated the inviting party’s unfamiliarity with his views, he would refuse to go. Many of his research students were reduced to tears by this same refusal to take shortcuts. While other supervisors were eager to usher their students rapidly through their research degrees in order to swell their bags, Uberoi would inevitably hamper the progress of his own through this same refusal to make concessions.

Despite this, all his pupils have continued to love and admire him throughout their careers, even those who abandoned him for less demanding mentors. His refusal at academic and ethical compromise made him demanding and difficult, but he was simultaneously a most caring and gentle human being who went out of his way to help not only students but many others in times of difficulty. However, if one needed a book that he possessed he would refuse to lend it, saying he wanted you to find out where another copy existed in the country. Despite being short of means he could be extremely generous. He once invited a professor from the UK to a sumptuous dinner at a grand hotel in Delhi and spent three weeks’ of his salary doing so. When visiting the same professor much later in London, his English counterpart, blessed with a far grander income, thought it would be impossible to return the favour in one evening but they went out to try and succeeded at four in the morning.

Uberoi was born in Lahore, the son of Mohan Singh Diwana, an eminent scholar of Punjabi literature and culture. Part of his unique intellectual ability owes to his having started out in electrical engineering at the University College, London, and then switching to anthropology at Manchester University after discovering from reading a friend’s anthropological paper that this was something he did ‘all the time’. Thus, his intellect combined the precision of a scientific mind with humanistic imagination and observation. The intricacy of some of his analytical figures are indeed reminiscent of circuit diagrams.

His life partnership with the esteemed professor Patricia Uberoi was not only a relationship of shared domesticity but of a shared, mutually stimulating intellectual space.

He is a man who has done great service to the cause of independent sociology in India, to the swarajist quest, and to the debunking of commonly held academic assumptions. May his work continue to inspire us all.

Khalid Tyabji was a student of Professor Uberoi during his M.A., M.Phil, and doctoral research on European science from 1977 to 1992. Primarily known for his performances on stage, street, and in special institutions, he has occasionally appeared in films. Additionally, he served as a visiting professor at the National School of Drama in Delhi for several decades. Tyabji is also a translator and co-editor of Acting with Grotowski (2015) and has compiled and edited Professor Uberoi’s Mind and Society, published by Oxford University Press in 2019

https://thewire.in/the-arts/remembering-prof-jps-uberoi-as-a-scholar-mentor-and-teacher

An Antim Ardas for Professor Jit Pal Singh Uberoi (1934-2024)

The hardest part of living away from India I find is to receive news of the passing of those one loved because one grieves alone, without the company of others who share your pain and who can recognise your loss. Today (January 6) is the antim ardas for Professor Jit Pal Singh Uberoi’s soul following on the cremation of his body yesterday. I sit far away in London from those meaningful events of mourning in Delhi, but offer my own personal antim ardas for Jit, with thanks for having the most profound influence on my intellectual development.

I knew JPS (as he was universally known) for over four decades in a variety of different ways. First, as his daughter Zoe (then Simran) and my sister Krittika learnt classical Russian ballet in the House of Soviet Science and Culture together. Simran’s family was like ours – all of us were present in the audience when our beautiful girls danced in a show and Safina and I bumped into each other frequently as we collected our sisters after class.

But I met JPS properly when I went to study a two-year Masters at the Department of Sociology. Those were arguably the best days at D School – JPS taught alongside Andre Beteille, B.S. Baviskar, A.M. Shah, Veena Das, a young Amitav Ghosh and so many other brilliant professors. The degree we studied had been designed by these pioneers whose vision of an India-trained anthropologist/sociologist was one in which the Sociology of India was understood thoroughly taking in everything from village kinship to labour and trade union dynamics, while being solidly trained in sociological theory, structuralism, symbolism, social inequality and kinship. That training was the bedrock on which we built our future scholarship and made us fearless in our engagement with writing from anywhere in the world. PhD students like Deepak Mehta, Savyasaachi, Khalid, Roma Chatterjee, Harish and others were always around for a chat, counsel and advice. In the second year, a bunch of us mustered courage (encouraged by our seniors) to try and persuade JPS to teach a course on South West Asia (that had been on the books but not been taught for many years). We were successful and it was transformative in how we saw the world.

Jit had written his own PhD thesis after fieldwork in Afghanistan and through a series of brilliant binary contrasts and eye-opening readings, JPS reoriented our thinking about the region (that those living west of the Suez call the Middle East) – and for me personally, allowed for my first encounter with the anthropological literature on Pashtuns/Pukhtuns/Pathans. A few weeks into the course in January 1988, Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan (Frontier Gandhi) the leader of the non-violent Khudai Khidmatgar movement died. I recall a conversation with JPS vividly – he like our professors, was always available for a chat outside the D School café after lectures – I wanted to write an op-ed piece for the papers pointing out the irony of a ‘martial’ race conducting the longest Gandhian movement in the world. His reply was, ‘Think about the idea some more; you may want to work on this for a longer research project.’ I was impatient but the anecdote he narrated of having seen Gaffar Khan once, flanked by two strapping Pathan men in brilliant red uniforms, stayed with me.

I am glad I moved away to Oxford for my PhD where I could work on the Khudai khidmatgars (it had been turned down at D School as logistically impossible to go to NWFP in Pakistan. (‘If it was possible Mukulika, would one of us not have done this by now’ were the exact words of the committee). At Oxford people vividly remembered Amitav Ghosh who, like JPS, had conducted his PhD research outside India in Egypt, and having been taught by both of them I felt I was part of an honourable tradition. But I went back to Delhi frequently (as I continue to do) and made it a point to see Jit on every visit to discuss ideas and writing. He was my most important interlocutor and helped develop ideas on the non-violence of the Muslim Khudai Khidmatgars in profound ways but also on pretty much everything else. It was a much better relationship than to have been his PhD student – I got the best without dealing with the worst! And it also allowed me to admire and interact with him on terms that British universities had taught me to – with deep respect, no fear and a great deal of affection. ‘Congratulations on your tour de force’ on an offprint he gifted me was a rare compliment.

My first job at UCL allowed me to call him ‘Jit’. We were now colleagues and he was chuffed that I was at the university he had studied in. It was then that I heard his personal observations of studying engineering, living in England and about his move to Manchester. His own deep scholarship on Europe and personal experience, gave me an intellectual confidence of living and engaging with my adopted country as nothing else did.

In 1996 Jit and Patricia attended my wedding to Julian. Jit observed: ‘In my generation, we mostly took brides from abroad, in yours we give our daughters too.’ And he was present too for my daughter’s onnoprashon as Safina his daughter and my dearest friend was now Aria’s godmother. In December 2022, I saw Jit in person for the last time. He and Patricia now lived in the apartment opposite my parents’ flat at Sah Vikas. I had just been on the Bharat Jodo Yatra and on the first morning back I walked over with a cup of tea to theirs to chat. My parents had passed away, but here were two people who heard the stories and asked after Aria and Jules as they used to. The stories of the Yatra provoked memories of nation-building and institution-building that Jit had been so committed to and our conversations meandered as they always did between profound thought, questions and laughter.

On this day, as the last prayers for Jit are said, I can only write my own antim ardas for Jit from the solitude of my desk. I cannot be with friends and colleagues who loved and admired Jit as I did, but I have a huge trove of memories of the time spent with this most remarkable man. Jit striding into D School every morning in his black turban that he readopted in 1984 riots, attending my first political demonstration with Jit at Ramlila maidan, Jit reading in Ratan Tata Library at the same desk every day after his retirement, Jit pointing out the use of sunlight for sanitation in Shahajanabad, having dinner with Jit in London, Jit’s face lighting up at Karim’s as Craig Calhoun, then Director of LSE said hello to him with the charming ‘Max told me to grow up and be like you’ (they were both students of Max Gluckman), Jit narrating detailed gossip of the Manchester School on Zoom calls during the pandemic while I completed my last book, Jit telling us about his fieldwork in Afghanistan as it was yesterday, Jit laughing as Patricia and Julian sang the Australian anthem at the birthday parties of Safina’s husband Lukas and Aria, Jit giving me a hug and kissing both cheeks the last time I saw him.

Jit, thank you for your scholarship, your provocations, your affection and your belief in me in carrying forward your legacy of political anthropology. I have met many brilliant people over the years but you have been the most important and most original of them all. Your students loved you much and continue to do – as we all said in the annual birthday Zoom calls on 5th September – and many will remain inspired and inspire future generations with what we learnt from you. May your soul rest forever in peace.

Mukulika Banerjee teaches anthropology at LSE and her most recent book is Cultivating Democracy (2021)

https://thewire.in/society/an-antim-ardas-for-professor-jit-pal-singh-uberoi-1934-2024

***********************************