Both Perestroika and Thatcherism, then, meant scaling back economic and social security to drive efficiency gains and shift labor and capital from declining to rising industries. If this similarity between East and West is unsettling to readers today, it is nonetheless one that, as Bartel’s archival work demonstrates, was recognized behind closed doors at the time… More than just fascinating history, the book makes a profound theoretical contribution. It demonstrates the importance of two institutional features of democratic capitalism, which state socialism lacked: the polity-economy distinction and competitive elections.

Max Krahé

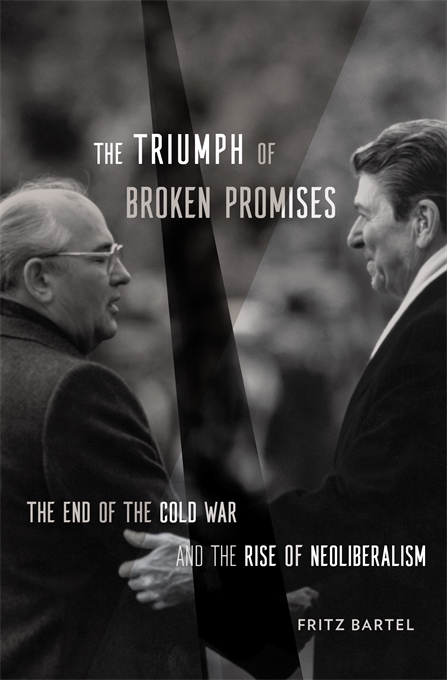

On Fritz Bartel’s The Triumph of Broken Promises

The Triumph of Broken Promises

By Fritz Bartel

The Triumph of Broken Promises by Fritz Bartel is a new history of the end of the Cold War. Challenging conventional narratives that focus on Reagan’s military-ideological assertiveness or Gorbachev’s openness to reform, the book gives a material and structural explanation of Western victory and Eastern defeat.1 This makes for fascinating history: finance and energy emerge as silent but vital battlegrounds, unlikely connections—like those between Japanese investors and Hungarian central bankers—come to the fore, and several East-West similarities surprise the reader.

More than just fascinating history, however, the book makes a profound theoretical contribution. It demonstrates the importance of two institutional features of democratic capitalism, which state socialism lacked: the polity-economy distinction and competitive elections. It also highlights the importance of neoliberal ideology, providing certain Western policymakers with a framework to justify and even praise the unraveling of social democratic Keynesianism, while Eastern leaders struggled in vain to legitimize a similar turn to austerity within state socialism.

These features help explain why the West won the Cold War, and why this victory coincided with–and was in part fueled by—the rise of neoliberalism. In tracing their impact, the book also speaks to a set of wider questions: what is the nature of capitalism’s recent crises? What are the implications for progressive politics today? And is capitalism vs. socialism even the most useful framework for discussing these questions?

Promises had to be broken

Why did the Cold War end with the peaceful proliferation of liberal capitalism, and why did it do so in 1989–91, rather than a decade earlier or later? Some historians foreground President’s Reagan’s decision to confront rather than appease the USSR or Mikhail Gorbachev’s “new political thinking.” Others “focus on the rigid economic stagnation of the Eastern Bloc during the 1970s and 1980s,” separate from and in contrast to an unproblematically prosperous, dynamic West.2

Bartel presents a different history, drawing on new archival evidence from West Germany, Britain, and the US on the one hand, and Poland, Hungary, East Germany, and the Soviet Union on the other. His account highlights shared (economic) problems rather than unique (Western) prowess. It stresses structural factors—growth, finance, energy—rather than the contingencies of individual choices.

“Contrary to the confident predictions of both democratic capitalism and state socialism” runs the opening gambit, “economic growth in both systems severely stagnated” in the 1970s and 1980s.3 Indeed, the book reminds us, it was the West that looked weaker to contemporary observers: “Could democratic leaders solve the riddle of stagflation if it meant inflicting pain on those they governed? Smart money said no.”4 In its emphasis on economics, on shared challenges, and on Western trouble, this is a refreshing and new take.

The East and West faced similar challenges, and their respective analyses and responses to it were similar too. Analyzing politburo transcripts and internal memos, Bartel shows how both sides reached the same diagnosis: decades of promises made and delivered had woven a dense tapestry of contracts and expectations, all premised on high future growth rates. Given that those growth rates had declined, leaders on both sides regretfully observed, the promises built on them had become untenable. The upshot: promises had to be broken.

Built on this shared diagnosis, Bartel shows there was also “a fundamental similarity between the quintessential project of neoliberal reform, Thatcherism, and the seminal project of socialist renewal, perestroika.”5 Both aimed at “carrying out painful domestic economic reforms in the hope of relaunching economic growth.”6

That Thatcherism meant a “fall in living standards; yet more unemployment” and a direct confrontation with the trade unions7—in the hope that “10 years of vulgarly pro-business and pro-industry policies” would boost investment and move labor and capital from declining into rising sectors8—is well known. More surprising may be Bartel’s finding that the East was pursuing a similar project: Soviet economists stated bluntly that Perestroika would replace “administrative coercion” with the “economic coercion” of the market9 and “lamented the ‘structural fatigue’ of their industrial economy and the ‘egalitarian mood’ of their population.”1011 To be sure, Gorbachev and other Eastern leaders were looking for a way to relaunch growth without social pain: “As a country where power is in the hands of the workers… it is natural that we should want to have no unemployment.” But unable to find one, Gorbachev himself had to concede that “Unemployment… will inevitably follow in the course of Perestroika.”12

Both Perestroika and Thatcherism, then, meant scaling back economic and social security to drive efficiency gains and shift labor and capital from declining to rising industries. If this similarity between East and West is unsettling to readers today, it is nonetheless one that, as Bartel’s archival work demonstrates, was recognized behind closed doors at the time.13…..

https://www.phenomenalworld.org/reviews/broken-promises/

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Noam Chomsky: The End of Organized Humanity

Trump’s Christian Fascists and the War on Palestine

The Mask is Off. After Ukraine, imperialism is now the norm

Collapsing Empire: Collateral Murder and the Delusion of US Air PowerThe Secret Military History of the Internet

Kojin Karatani’s theorising on modes of exchange and the ring of Capital-Nation-State

The New Associationist Movement

Noam Chomsky: Savage capitalist lunatics are running the asylum

What I’ve learned from Noam Chomsky

The Pegasus Project: Leak uncovers global abuse of cyber-surveillance weapon / Shoshana Zuboff: The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

Welcome to the Age of Technofeudalism: Yanis Varoufakis interviewed by WIRED magazine