Siut Wai Hung Clarence

A map of the spread of Manichaeism (300–500). World History Atlas, Dorling Kindersly.

At first glance, the sculpture residing in the Cao’an temple in Jinjiang of the Fujian province seems to be just another statue of Buddha. The stone inscription outside the shrine calls the figure Moniguangfo, or Mani, the Buddha of Light. In the 1950s, locals in the area also told archaeologist Wu Wenliang that the sculpture was indeed Buddha, thinking that the name Śākyamuni (the title of Buddha) was mistakenly translated to Moni.[1] Today, Buddhist monastics care for the temple and use it for Buddhist worship.[2] However, Wu concludes that the statue is not Buddha. For one, the sculpture sports a beard and “does not have any curly hair on his head”.[3] Coupled with other reasons, Wu finds that the sculpture is instead Mani, the founder of Manichaeism.

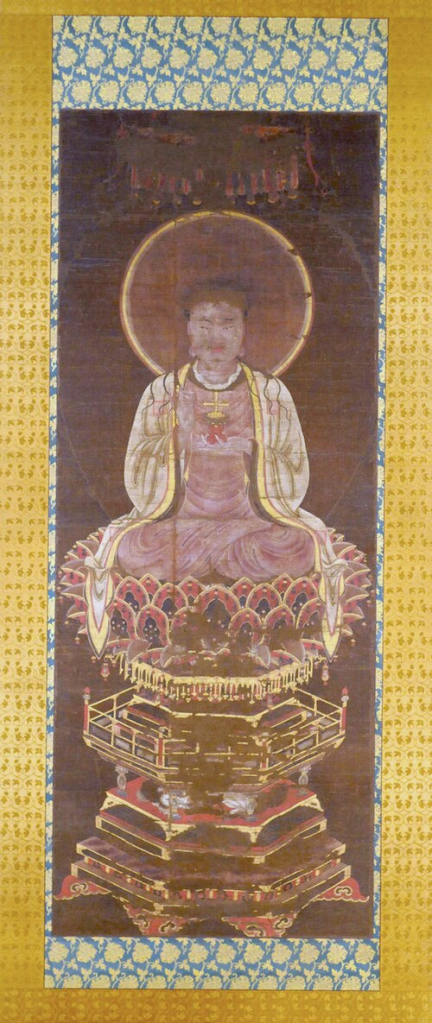

Manichaean Painting of the Buddha Jesus depicts Jesus Christ as a Manichaean prophet. The figure can be identified as a representation of Jesus Christ by the small gold cross that sits on the red lotus throne in His left hand. (Source: Wikipedia)

This raises several questions: Who is Mani? Why does he look like Buddha? How did Manichaeism spread to China? In this essay, I argue that Manichaeism survived and spread in imperial China by co-opting terms and motifs from Chinese Buddhism in Manichaean text and art. In the following sections, I first briefly detail the origin of Manichaeism as a religion, its beliefs, and a timeline of its rise and fall in China. Next, I use the works of various authors to show how Manichaeans borrowed Buddhist terms and motifs by examining Chinese Manichaean texts and artwork. I then provide some concluding remarks.

Manichaeism: Origins, Core Tenets and Spread to China

In 216, contemporaneous with the Han Dynasty in China, the founder of Manichaeism, Mani, was born in Babylon.[5] He was born into the Elchasitic Baptism sect of the Christian faith and practised it for the first 24 years of his life.[6] However, Mani had many disagreements with the sect on food taboos and rituals.[7] For instance, he did not agree with the Baptists’ practice of baptising vegetables as he thought they would damage the light particles within the vegetables.[8] Mani was also said to have received two separate revelations from his spiritual “Twin”, who exposed the “true” nature of the universe to him.[9]

Upon receiving his second revelation at 24, Mani left his sect and began preaching his teachings to different parts of the world. His teachings greatly amalgamated pre-existing world religions. Specifically, Mani saw himself as the final messenger of God, alongside prior messengers of Jesus, the Buddha and Zarathustra (from Zoroastrianism).[10] Mani even gained the patronage of the Sassanian king Shahpur, who used him as the gel for uniting the major religions of Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and Christianity within the Iranian empire.[11] While royal patronage continued under Shahpur’s son Hormizd I, Mani was later prosecuted by Shahpur’s grandson Bahram I, where he died in captivity after twenty-six days.[12]

The core beliefs of Manichaeism are the “two principles and three epochs”.[13] More specifically, Manichaeans view the world as a constant battle of the two principles of light and darkness across three epochs, namely the primordial, the present and the future. Light and darkness are represented by the opposing forces of God and matter respectively.[14] Hence, Manichaeans aim to quell matter they believe to be evil by abstaining from meat, marriage, sex and reproduction.[15] Manichaeans also worship the sun and moon as vehicles that allow them to access God.[16] The adherents of Manichaeism can be split into a lay following, known as the hearers, and a monastic order known as the elect.[17] In terms of organisation structure, Manichaean authority flows down from the leader to the twelve teachers, to the bishops, to the elders, and finally to members of the elect.[18]

After Mani’s death, Manichaeism began to spread in multiple directions. Spreading West into Rome, it was heavily suppressed by the 4th Century, with Roman Emperor Theodosius I issuing edicts to persecute Manichaeans beginning in 382.[19] It also spread to Central Asia and China via Sogdian merchants who traded with the Chinese and the Pamirs along the Silk Route.[20] Lieu mentions that the Sogdians were “fervently evangelistic” as they spread Manichaean teachings among the Han Chinese since the 7th Century.[21] Manichaeism was first reported in China during the Tang dynasty, where a Manichaean cleric was recorded to have visited China during the reign of Emperor Gaozong (650-83).[22] Later in 694, a Persian bishop with the title of Fuduodan presented Empress Wu Zetian with a religious text called the Book of the Two Principles, or erzongjing.[23] Yet, the Manichaeans likely established a presence in China even before the 6th Century.[24] For instance, Manichaean presence is spotted on the funerary monument of Shi Jun, a Sogdian leader who served as caravan leader in the Northern Wei dynasty and died in 579.[25]…..

https://blog.nus.edu.sg/imperialchina/2021/12/23/research-2021-4/

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Tracing the Hard Edges of Religion: On Peter Brown’s “Journeys of the Mind”

Christianity, Violence, and the West

The Secret History of the Mongol Queens

Book review: Pleasure Domes and Postal Routes – How the Mongols Changed the World

A Medieval Age of Disruption: On Nicholas Morton’s “The Mongol Storm”