An Indonesian songbird once nearly extinct in the wild, the Bali starling, is making a comeback through community-led conservation on Nusa Penida and beyond.

NUSA PENIDA, Indonesia — Two young conservation workers rattle up on a motorbike and dismount at the edge of a coconut grove. Picking through husks, fallen fronds and stray plastic bottles, they scan the canopy, waiting in stillness.

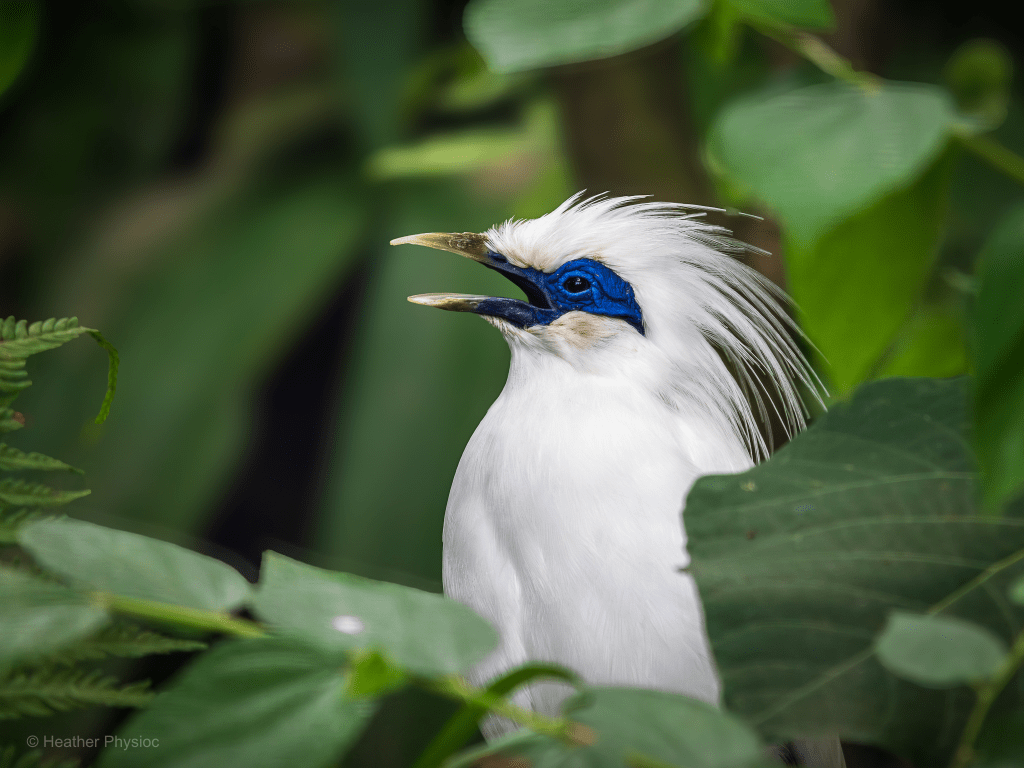

A Bali starling sings with its beak wide open, showing its striking cobalt-blue facial skin and wispy white crest feathers. Once nearly extinct in the wild, the starling is making a comeback. Image by Heather Physioc.

For nearly 20 minutes, nothing stirs. Then, a flash of white. A Bali starling (Leucopsar rothschildi) pokes its head from the hollow of a dead palm and darts into view before settling on a nearby branch. Moments later its mate follows, the pair taking turns caring for the nest and foraging for food. This natural cavity nest, which sits beside an artificial nest box, is only the second ever recorded on Nusa Penida, a small island off the coast of Bali.

This family of starlings, also known as Bali mynas, are among the world’s rarest birds, endemic to Bali and once reduced to just six individuals in the wild.

Each sighting marks a sign of hope for a species making a cautious comeback through community leadership, cultural tradition and grassroots conservation.

The near collapse of the Bali starling

Songbird-keeping surged across Indonesia in the mid-20th century, driven by migration, rising incomes and competitions that elevated melodious birds as status symbols. The Bali starling, prized for its striking white plumage and distinctive call, became a coveted target for collectors and trappers.

Despite official protections dating back to 1958, weak enforcement across the archipelago allowed a lucrative trade to flourish, fueling an economy of trappers, breeders, trainers and cage sellers. Strict bans have sometimes backfired, making ownership of the illicit birds a mark of prestige among elites, a 2015 study in the journal Oryx reported. At its peak, the caged-bird industry was valued in the trillions of rupiah.

With porous borders, thousands of islands and limited resources, traditional enforcement methods struggled to keep up with massive and global demand. Even when authorities manage to confiscate trafficked birds, they often die in captivity from the trauma, stress and lack of immediate care.

Adding to the starling’s difficulties, land conversion for agriculture, settlements and tourism infrastructure accelerated deforestation and habitat loss, relegating the species to isolated pockets, making it more vulnerable to threats like predation.

The crisis reached its most desperate moment in 2001, when only six known wild individuals remained. Even more dire, this unique species of myna is the only vertebrate endemic to Bali that remains after Dutch hunters shot the last Bali tiger in 1937.

Traditional, top-down conservation achieved limited success

In the mid-1980s, the International Council for Bird Preservation (later BirdLife International) and the Indonesian government formed a coalition that established objectives for monitoring the species, restocking wild populations, establishing breeding programs and raising public awareness. Breeding efforts were successful, but weak oversight and unclear success metrics hindered post-release outcomes, which were poorly monitored, according to an analysis in Biodiversitas.

The Tegal Bunder Breeding Center released 218 birds into Bali Barat National Park (BBNP) over 18 years, but the wild population continued to plummet. Many failed to survive, lingering near release sites, showing continued reliance on humans and becoming easy targets for poachers.

Park rangers increased patrols, yet poaching continued relentlessly in the forest, and 78 birds were stolen from a breeding center in the national park. A pair of birds could command a black market price up to 40 million rupiah in the 1990s (about $4,500 at the time), years’ worth of salary for a park ranger, making it easy to pay off officials if needed.

“The crucial point was that this Western approach had a need to protect, ramp up enforcement, monitor it, and it wasn’t really getting anywhere,” said Paul Jepson, who led the BirdLife Indonesia program in the 1990s. “It wasn’t solving the decline.”

BirdLife donors eventually lost confidence, and the NGO withdrew from the initiative by 1994.

The songbird trade remains a significant source of income for many Indonesian communities, with the caged-bird sector estimated to be worth billions of U.S. dollars. In some communities, a single forest sustains the local economy. Bird-catching is how people put food on the table, send kids to school or pay for health care in an emergency. When less extractive alternatives do not offer clear financial incentive, people resort back to the forest.

“Local communities tend to think and act pragmatically,” said Marison Guciano, founder and executive cirector of FLIGHT, an NGO founded to combat the regional songbird trade. “Meeting basic community needs must be a priority. Conservation efforts are not only about protecting and preserving wildlife and forests, but also building and improving the welfare of local communities.”…

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++