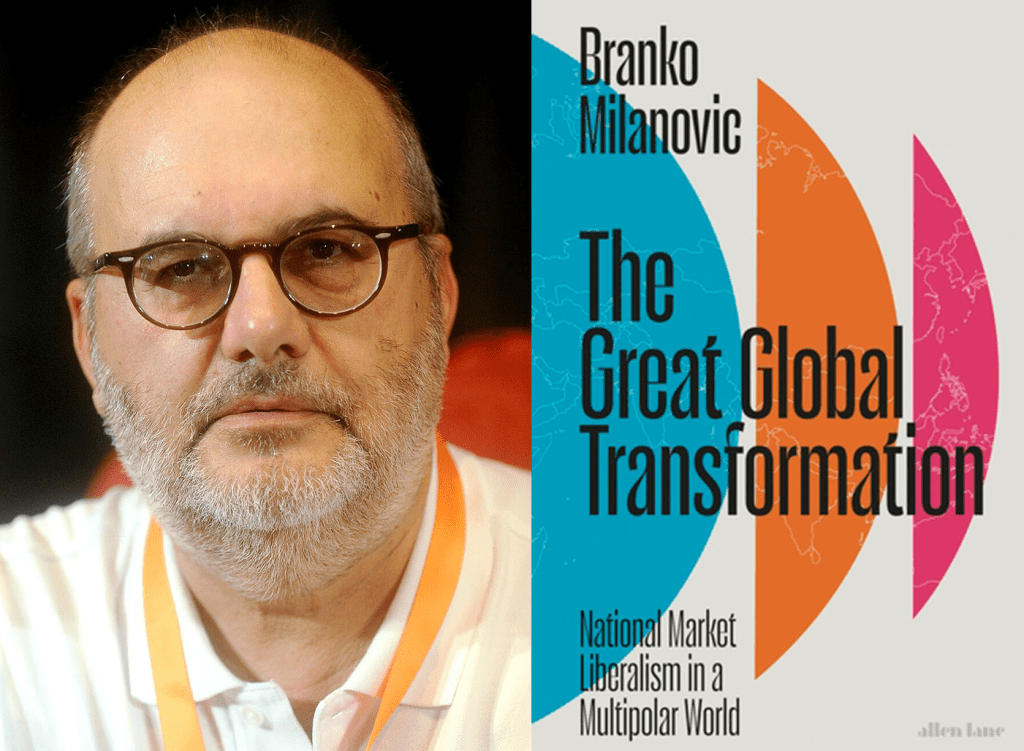

The Serbian-American economist Branko Milanović has emerged as one of the most discerning thinkers of our time – and certainly one of the most productive. In his books since 2016, he has moved from measuring global inequality to theorising capitalism’s competing forms to excavating how we’ve historically thought about inequality. His new book, The Great Global Transformation, studies the emerging multipolar geopolitical order.

Reading these books in sequence, one gets not just an analysis of global capitalism but of the major events of the last decade: Brexit, Trump, Covid, Ukraine, the China-US confrontation. Equator’s Gavin Jacobson talked to Milanović about the themes of his new book.

Is there something about the Balkan or Eastern European experience that generates particular insights into our current multipolar moment?

Growing up, it was the specific Yugoslav experience of Non-Alignment which changed me. I was in elementary school in the 1960s – the peak of Non-Alignment – when I became deeply interested in what you might call “the rest of the world,” the world of Ahmed Ben Bella, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Kwame Nkrumah and others. So a lot of my thinking, at least my interest in political and intellectual traditions outside the western liberal canon, can be traced to those formative moments.

More spectacular was the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1992. It was an enormous shock because we had to reinvent ourselves, redefine our identities overnight. I had no Serbian identity, and didn’t know anything about Serbian history. You suddenly find yourself asking: “Who the hell am I?” So this story about the “End of History”, of triumphant liberalism and multi-ethnicity, didn’t really fit with witnessing the breakup of a country along ethnic lines.

After I joined the research department of the World Bank in the early 1990s, I spent a lot of time working in Russia. That’s actually when I stopped reading the mainstream media because what it published at that time about the post-Soviet world was beyond risible. I was in Moscow when “shock therapy” was pulling society apart. You had impoverished professionals on the streets desperately trying to sell things to make some money, and then you read the New York Times proclaim: “Freedom works!” It instilled an unshakable scepticism in this liberal narrative about capitalism, markets and progress.

You’ve not read any mainstream media since the 90s?

I’ve certainly not gone near the New York Times in about 20 years.

Your new book, The Great Global Transformation, makes a compelling case that the US is in relative decline. But American political culture seems remarkably resistant to processing this development. We get denial (“China will collapse”), nostalgia (MAGA) or threat inflation (“new Cold War”), but rarely sober acceptance of a multipolar world. Why has it been so difficult for the US to come to terms with what your data shows?

It’s due to a view of the world acquired after the Second World War, when American elites came to see the US as a power that battles all kinds of dictatorships – the “arsenal of democracy,” “the indispensable nation” (to quote Madeleine Albright).

It is important, though, to note that US elites did not entertain the same view prior to 1941, and certainly not prior to the First World War. The US then behaved very much in accordance with what one expects from a regional power. It controlled the Dominican Republic and Cuba, colonised the Philippines, and took large chunks of territory from Mexico – but did not exhibit a worldwide vocation.

So it’s not impossible that American elites might return to that anterior view of the world: in short, to the Monroe doctrine, but not more than that. I can’t be sure, of course, because China represents such a unique problem for American power, but I’m generally not a huge fan of declinist theories about “the end of the West.” It’s just going to have to accept that it’s one pole among many.

The economic historian Adam Tooze recently said that “China isn’t just an analytical problem, it is the master key to understanding modernity.” Do you agree with that?

I suspect Adam may have been responding to a recent and very interesting article by Kaiser Kuo called “The Great Reckoning,” which examines China at a completely different level to the usual coverage. It’s not about “who’s going to replace Xi Jinping?” or “Will China grow by 6% or 3%?” but rather showing how China, on its own terms, is defining what it is to be modern. And even more significantly, it is projecting an alternative picture of modernity which is no longer mimicking western modernity. The article is actually Fukuyama-esque in its historical implications.

Is there a direct line from Yugoslavia’s disintegration to your current work on competing capitalisms and the multipolar world?

I think there was a line, yes. But it took me a long time to figure this out. Early on – this would have been 1992 or 1993 – I wrote an article about how globalisation might come to an end. I sent it to Monthly Review and they rejected it.

The piece drew on my interest in Roman and Byzantine history. I saw Roman globalisation as the first globalisation, with striking similarities to the American-led version we were living through. Latin and Greek were the lingua franca. The Gospel was written in Greek and translated into Latin precisely to spread it across the empire. And eventually, Christianity – the very thing that had unified the empire – broke it apart.

I was trying to think through similar dynamics in contemporary globalisation. I’m not claiming I predicted what would happen, but I had doubts very early on that globalisation, as conceived during the “End of History” moment, was sustainable. And these doubts came partly from what I was observing in Yugoslavia – developments that ran completely counter to what was supposed to happen. Multiculturalism was supposed to spread around the world making borders irrelevant while there we had federations breaking apart and wars being waged along the ethnic or religious lines.

I kept asking myself: Is this the last war of the previous century, or the first war of the new century? I couldn’t decide for a long time. Now I think it was clearly the first war of the new century. But at the time, it could have gone either way.

Equator <newsletters@equator.org>

************************************

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes and the Death of Freedom

‘Here lives the monster’s brain’: the man who exposed Switzerland’s dirty secrets

Ntina Tzouvala, Capitalism as Civilisation: A History of International Law

Lynn Paramore: Our Economic System is Making Us Mentally Ill

The New Associationist Movement

Kojin Karatani’s theorising on modes of exchange and the ring of Capital-Nation-State

Retotalising Capitalism: A Very Short Introduction to its History

Noam Chomsky: Savage capitalist lunatics are running the asylum

Noam Chomsky, The Responsibility of Intellectuals (1967)

What I’ve learned from Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky: The End of Organized Humanity

Welcome to the Age of Technofeudalism: Yanis Varoufakis interviewed by WIRED magazine