Lou Salomé was undoubtedly one of the most intelligent and articulate women of her era. Her own writing, especially her essays on sexuality and erotism, have value not merely in their historical reflection of the era in which they were written, but in their own right as documents of radical femininity in the fin-de-siècle and as a documentation of the recognition of the unique and equal power of women. Lou refused to live according to the rules and values of the bourgeois society of the time, and participated in the intellectual life of her time to an unprecedented degree – not merely as Nietzsche’s and Freud’s disciple and Rilke’s muse – but in her own right as a writer and as a psychoanalyst. After reading her essay “Psychosexuality” of 1917, Freud, not known for his flattery or charitable readings of others’ work, remarked in his letter of November 22, 1917: “I am constantly amazed at the art of your synthesis, which is able to integrate the various disjecta membra achieved through your analysis, and then envelope them in a living whole.”

“In the background of all of his feelings for a woman, a man still has contempt for the female sex.”

“The human being is too imperfect a thing. Love for a person would destroy me.”

“In every conversation between three people, one person is superfluous and therefore prevents the depth of the conversation.” — Friedrich Nietzsche

These quotes from Nietzsche’s Tautenberger Aphorismen during the summer of 1882 make clear that Nietzsche was, at the very least, deeply conflicted about his ability to connect with another person. When that other person was a female in Nietzsche’s life, the matter becomes complex. Finally, when the female is a friend of Nietzsche’s friend and is basically installed as the missing component of a love-triangle, the situation becomes even more difficult.

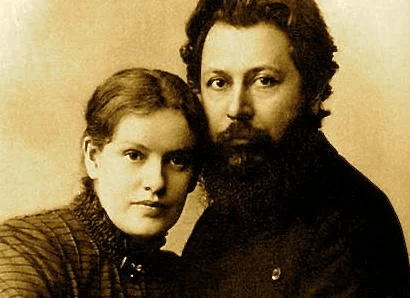

Lou Salome with her husband, Friedrich Carl Andreas; c.a 1885

Many studies have grappled with the “problem” of Nietzsche and the feminine, Nietzsche and female sexuality, and Nietzsche and the actual women who were significant in his life, yet few, with the exception of the Irvin Yalom’s novel When Nietzsche wept (1993)– a fictitious philosophical reconstruction of Nietzsche becoming a patient of Josef Breuer’s at the behest of Lou Salomé — have focused in on what is perhaps the most significant relationship to a woman (other than the extremely conflicted relationship to his sister) that Nietzsche experienced. Of all the women who figure prominently in Nietzsche’s life, Lou von Salomé was the most important woman to befriend him, and one of the powerful forces that operated in the last decade of the philosopher’s active life. How this relationship was both informed by Nietzsche’s thought, and how in turn its failure and the pain it caused influenced Nietzsche and contributed to his ever-deepening depression and isolation has not been fully traced.

From the historical record, this much is certain. Friedrich Nietzsche first learned of Lou Salomé from his friend Paul Rée, who had met Lou at the home of Malwida von Meysenbug in Rome on the 13th of March 1882. Von Meysenbug often hosted writers and thinkers of the time. Rée wrote to Nietzsche about Lou and, although Rée’s letter has been lost, we can only assume from Nietzsche’s response that Rée must have been extremely enthusiastic about Lou from the beginning. Nietzsche wrote back to Rée: “Greet this Russian woman for me, if this makes any sense; I long for this type of woman, I’m even thinking about plunder in this regard, when I think about what I want to do in the next ten years. Marriage is a totally different matter. I would only be interested in a two-year marriage, and this, again, only in view of what I have set out for myself over the next ten years.” Student, confidant, discussion-partner for philosophical ideas, erotic object, and finally femme fatale, the 21 year old Lou was to play many roles for the older author of The Birth of Tragedy. Nietzsche fell in love with Lou instantly, and proposed marriage three times during a seven month period. Nietzsche was enormously difficult by any standard, but this should not obscure Lou’s own unique contribution to the short, doomed relationship, nor lessen the significance of the failed relationship for Nietzsche’s subsequent depression….

Nietzsche’s preliminary response to Rée’s letter, while surprising in its direct, forward nature, can be understood in the context of his longing for a disciple, perhaps even comrade in ideas, and reveals much about Nietzsche’s mindset and vulnerability to a relationship that was problematic from the start. Although he stated that he would only consider short-term marriage, there is evidence to suggest that Nietzsche might have been seeking a Lebensgefährtin, a soul-partner to accompany him on his philosophical journey. He was also being provoked through the communiqués of a number of different people, especially Malwida von Meysenbug. Of the many voices that resonate in the history of this complicated relationship, and the many people that were to become involved in this affair, Malwida von Meysenbug was to play a pivotal role. She, perhaps even more than Reé, set the stage for the drama that was to unfold between Nietzsche, Lou, Rée, and Nietzsche’s vindictive and jealous sister, Elisabeth, who later married the anti-Semite Bernard Förster, became a bitter enemy of Lou Salomé, and attempted to falsify much of Nietzsche’s writing. We owe it to Karl Schlechta for having shown the degree to which Elisabeth altered her brother’s œuvre for her own ideological and political purposes.

On the 27th of March, 1882, von Meysenbug wrote to Nietzsche: “A very strange girl (I think Rée wrote to you about her) to whom I indebted, among many others, for my book; she appears to me to have arrived at the same results in philosophical thinking as you, that is, towards a practical idealism, leaving behind every metaphysical presupposition and every concern about the explanation of metaphysical problems. Rée and I agree in the wish to see you with this extraordinary person, but unfortunately I can’t recommend a visit in Rome because the conditions here would probably not do you well.” Cognizant of Nietzsche’s frail health and susceptibility to “attacks” of various kinds, she was afraid Nietzsche would fall ill in Rome….

In January and February of 1883, Nietzsche emerged enough from this depression so that he was able to write the first part of Zarathustra in ten days, with the other parts to follow in similar bursts of writing in 1884 and 1885. The period between the break from Lou and his final breakdown in 1889 was one of the most productive of his life: Beyond Good and Evil (1886), The Genealogy of Morals (1887) and Ecce Homo (1888) are other examples of this enormously productive period. As his mental illness increased, so did his denial. From the initial diagnosis in 1889 at the Nervenklinik in Basel until his death on August 25, 1900 in Weimar, Nietzsche was cared for first by his mother, and then, after her death in 1897, by his sister Elisabeth. It is believed that for those eleven years, Nietzsche understood very little of what was transpiring around him.

The great diagnostician of European Nihilism, whose historical erudition and philosophical rigor had distinguished him as perhaps the most important thinker of the 19th century, himself became encapsulated in an isolated chamber of delusion and oblivion. Speculations of mental illness brought on by advanced syphilis have abounded, and yet the trauma of the failed love relationship with Lou, and its unresolved tentacles, strike me as a more plausible explanation for Nietzsche’s demise. If mourning and trauma without an empathetic witness, solidarity, compassion and working-through via transitional objects mark the beginning of madness, Nietzsche’s tears bear the mark of the ongoing narcissistic wound formed by Lou’s rejection and Nietzsche’s own narcissistic vulnerability, his ‘madness’ a symptom of a profound unresolved trauma and the inability to find companionship or empathy in his mourning.

Read more: https://rsleve.people.wm.edu/FNLAS_1882.html

Always, in woman’s highest hour, man is only Mary’s carpenter beside a god – Lou Andreas Salome, 1910; in Die Erotik

Antony Hopkins plays Freud in Freud’s Last Session

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Tae-Yeoun Keum: Why philosophy needs myth

The Intellectual We Deserve (2018)

What is truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer

So history didn’t end after all

Julien Benda: Our age is the age of the intellectual organization of political hatreds

Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann – Repetition and rupture: Reinhart Koselleck, theorist of history